Canada Fieldwork Experiences

Karis Barker Bio

Karis Barker, MPH in Community Health Sciences student, traveled to Canada through the Global Health Program and completed her practicum experience with the Elizabeth Fry Society. She focused on program evaluation and research, assisting clients with immediate needs (referral to shelter, distribution of hygiene products/food/clothing), setting up talking circles for indigenous elders and clients, making traditional ribbon skirts and shirts and attending inter-agency meetings.

Karis Barker's Blog

Karis' blog post

Although I am a Canadian citizen, I wasn’t born here and I have never technically lived here.Until now, Canada has been a place that I visit relatives and do touristy things like hiking in the mountains or taking advantage of the favorable exchange rate while shopping at the mall. For years I have felt a sense of obligation that I should know more about this country that I have the right to call home. It’s strange to identify with a place so closely but understand it in such a limited way.

During the long weekend observing Canada Day (July 1st), I am more aware than ever of my ignorance as a Canadian citizen. There is a lot of political, historical, and cultural information that I just don’t know.

However, being in Canada as a practicum student, I am learning more of that political, historical, and cultural information that I never would have gotten as a tourist. I feel more Canadian and I finally feel like I can say that I’ve lived here. I have a daily routine, a commute, an office… I’ve been to the mall several times but I haven’t made it to the mountains yet because I’m not on vacation, I’m working. Even “eh?” has slowly crept into my vocabulary. I’m so grateful that I am fulfilling my practicum requirement in Canada because it is enhancing my public health perspective as well as my own sense of cultural identity. Working at the Elizabeth Fry Society of Calgary has added an additional layer of complexity to my understanding of Canada by introducing me to indigenous people and how Canadian identity has affected them. In the blog posts to follow, I will explore this topic in more detail.

.Commute - A view of Bow River, which I bike along to get to work

Commute – A view of Bow River, which I bike along to get to work

.Canada Day - A view of fireworks in celebration of Canada Day

Canada Day – A view of fireworks in celebration of Canada Day

.Calgary Tower - An iconic building in Calgary's skyline

Calgary Tower – An iconic building in Calgary’s skyline

Karis' blog post

Just as I am becoming more confident in my sense of Canadianness, I am realizing how Canadian identity has caused pain and trauma to Indigenous people. Until working at EFry, the unethical treatment of Indigenous people was just a unit in U.S. history class for me. I studied concepts like manifest destiny, reservations, and assimilation but in a distant, academic way. We didn’t really discuss how traumatic these concepts were originally nor their lasting consequences for Indigenous people.

Through my practicum, I learned some of the history of Indigenous people in Canada (unfortunately similar to the U.S.) from reading EFry orientation manuals but I am also seeing first-hand the intergenerational trauma and consequences of imposing Canadian identity. Interacting with EFry staff, volunteers, and clients who are Indigenous is helping me perceive their history no longer as distant and academic. I am getting to know them as individual people with powerful life-stories that you might never find in a textbook. Their wisdom, resilience, and passion for preserving their cultural identity despite so many obstacles are inspiring.

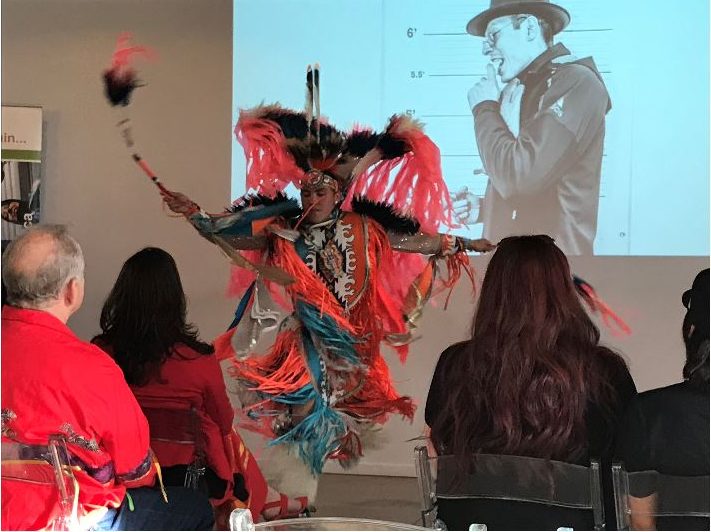

EFry’s Annual General Meeting (AGM) was an amazing opportunity to appreciate Indigenous culture through performances, stories, and interviews. It was both a festive and mournful experience. We celebrated the work that EFry is doing and the rich culture that Indigenous people maintain but we also remembered those affected by the Canadian government’s attempts to assimilate as well as Indigenous women who have gone missing or were murdered.

One of my greatest takeaways from the AGM was the distinction among labels of aboriginal, Indian, and Indigenous. Aboriginal sounds sophisticated and culturally sensitive but it literally means “not original”. The term suggests that the settlers who established Canada as we know it today were the ‘true’ original people even though they arrived long after people had already lived there. “Indian” caught on after Christopher Columbus thought he discovered India, although he actually stumbled upon the Caribbean. Indigenous appears to be the preferred term, derived from the Latin word “indigena”, which directly translates to “native”.

Within “Indigenous” there are sub-classifications of First Nations, Metis, and Inuit. First Nations people are descendants of the first people who lived in what is now Canada. Metis indicates a person who is of both First Nation and European descent (similar to the term Mestizo). Inuit people are Indigenous to Northern Canada as well as Greenland and Alaska.

.

The man pictured below is performing the Men’s Fancy Dance, which, as the regalia suggests, is a dance intended for entertainment.

.dance

Dance

Karis' blog post

Last Tuesday, I participated in a Blackfoot Language Class at the EFry office. Blackfoot is a language that many Indigenous people in Alberta speak; however, it is becoming less common as people increasingly rely on English to communicate. EFry offers Blackfoot classes that help keep the language alive and help Indigenous clients reconnect with their culture.

The session that I attended was different than usual because the Alberta Minister of Advanced Education was there as well as a representative from Calgary Learns, an agency that provides funding for adult education programs. The class was a wonderful opportunity to get an overview of the curriculum and learn some phrases and vocabulary. For example, we learned how to say “My name is…” and “What is your name?”

To say “My name is Karis” would be “Oki Niisto Niitaniko Karis”.

(O ghee) (nee sto) (nee duh nik goh) (Karis)

And asking “What is your name?” would be “Kiisto Tsa Kiitaniko?”.

(Ghee sto) (Tsa) (Ghee duh nik goh)

“K” sounds are pronounced more like “G’s” and “T” sounds are pronounced more like “D’s”.

The teacher’s explanation of the development of certain words was particularly interesting, especially for animals that are not endemic to Blackfoot-speaking regions.

For instance, horses were introduced to First Nations people by Europeans, so they had to come up with a name for this new animal: “ponokáómitaa”. The animal looked like the combination of an elk (ponoká) and a dog (omitaa), two animals for which they already had names. Therefore, the word for horse directly translates to elk-dog. Even some towns and cities in Alberta are derived from Blackfoot words. The town of Ponoka comes from the same word for elk: ponoká.

Karis' blog post

This past weekend I went hiking in the Rocky Mountains, which are a beautiful 1-2 hour drive from Calgary. Low humidity, sunny skies, and about 70°F weather made for a perfect mountain hike. I even got to see grizzly bear cubs driving back towards Calgary!

.AC

Animals crossing the road

.P2

View of trees and river