The Pandemic Behind Bars

Pandemic Behind Bars: Containing COVID-19 Outbreaks in Illinois Correctional Settings

Note: after the original publication of this report, the Cook County Sheriff’s Office provided additional information concerning the total number of detainees who came in contact with the Cook County Jail during the mid-March to mid-June period. This report has been updated to reflect the latest data provided.

All around the United States, prisons and jails have become hotspots for COVID-19. Inmates and staff working at state correctional facilities, and those living in the surrounding communities, are all at heightened risk of contracting COVID-19.1 The Illinois Department of Corrections (IDOC) is grappling with localized COVID-19 outbreaks and is likely to face more outbreaks if proactive measures are not taken to bolster self-hygiene, social distancing, and testing availability.

This Policy Spotlight documents the growing concern for the health of the incarcerated population and explores the implication of unabated prison and jail COVID-19 outbreaks for the health of Illinois communities where correctional facilities are located. It argues that jails and prisons are not isolated or removed from the community. Preventing COVID-19 transmission in jails and prisons requires steps to ensure that COVID-19 outbreaks within correctional settings do not spill over to the surrounding communities, and that infection does not enter into correctional facilities from the community. Meeting the public health and mental health needs of inmates is not only just, it is smart public health policy.

Download the full report

Outbreaks in Illinois correctional facilities Heading link

As of June 22, the Cook County Jail (CCJ) had reported 558 people who had confirmed cases of COVID-19. Of these, 527 have recovered, seven have died and 24 were currently positive. This is across a population of approximately 8,000 detainees,* the total number that had been held in the jail during the period mid-March to mid- June.2 Together, these account for 6.9% of CCJ detainees. CCJ employees have been hit hard as well. By June 22, 446 cases had been confirmed among the CCJ staff: 36 employees were positive for COVID-19 on that date, an additional 407 staff had recovered, and two correctional officers and one deputy had died due to COVID-19.3 This represented roughly 14.9% of CCJ’s workforce of approximately 3,000 employees.4

On May 29, 2020, federal judge Matthew Kennelly denied Cook County Sheriff Thomas Dart’s request to stay an April 2020 preliminary injunction in a class action lawsuit over jail conditions. The judge ordered the sheriff to implement a number of measures to protect inmates from COVID-19 infection. These ranged from ceasing to use “crowded bullpens” at intake to enforcing “social distancing in most of the Jail,” testing for symptoms, ensuring “actual” access to sanitation, and “enforcing cleaning and sanitation” throughout CCJ.5

Mitigation measures in correctional facilities affect not only the health of inmates but also that of the public. A study published in the journal Health Affairs documents that 15.9 percent of all confirmed COVID-19 cases in Chicago on April 19 were associated with cycling through CCJ, meaning that “arrest and pre-trial detention practices may be contributing to disease spread.”6 However, it is possible that CCJ infection rate simply reflects the number of people coming into the jail with COVID infection in the community, rather than transmission within the jail.7 Importantly, the majority of CCJ detainees are racial or ethnic minorities, which are populations that also are most affected outside jail by the COVID-19 pandemic.8 Policies to reduce transmission in jail can help minimize the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on minority communities.

In state correctional facilities, COVID-19 affects both the inmate population and staff. At 12 of IDOC’s 24 correctional centers across Illinois, 274 inmates had tested positive for COVID-19, of whom 225 had recovered as of June 22. The most recent information publicly available indicates 13 had died as of June 9.9

Staff are not immune to these risks. By June 22, 184 IDOC staff had tested positive, of whom 167 had recovered across the 24 facilities.10 Notably, some of the staff infection was among people who worked at IDOC treatment facilities, such as the Elgin, Joliet, and Kewanee treatment centers. None of these facilities reported any inmate cases.11

COVID-19 cases are not equally distributed across IDOC facilities. By June 22, Stateville Correctional Center and its Northern Reception and Classification Center (NRC) in Will County accounted for 68.2% of the total IDOC inmate confirmed cases (187 of 274 confirmed IDOC inmate cases).12

Additionally, 79 Stateville staff and 37 NRC staff have contracted COVID-19, of whom 108 have recovered. Stateville and NRC confirmed staff cases comprise 63 percent of all 180 IDOC staff cases as of June 22.13

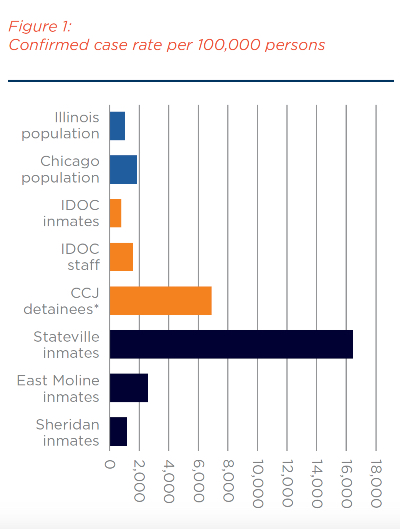

The confirmed case rate in some correctional settings is significantly higher than the rate in Illinois’ general population as of June 22, which is a rate of 1,082 per 100,000 persons.14 In the Stateville Correctional Center, for instance, the confirmed case rate for inmates is estimated at 16,447 per 100,000 persons (187 confirmed cases in an inmate population of 1,137),15 while for the staff the case rate is 6,049 per 100,000 persons (79 of 1,306 employees).16

Outbreaks in Illinois correctional facilities, continued. Heading link

Figure 1 provides a comparison of confirmed case rate per 100,000 persons among Illinois, Chicago, IDOC, and CCJ populations as of June 22.

Confirmed case rates at these IDOC facilities exceed case rates across Illinois. CCJ’s rate is more than six times that of surrounding Chicago (12,270 vs. 1,956 per 100,000 persons). The fact that the confirmed-case rates for certain facilities are at such high levels indicates that their con- ditions have not allowed effective mitigation or containment.

There are good reasons to believe that coronavirus was spreading inside IDOC facilities such as Stateville Correctional Center before IDOC report- ed its first COVID-19 inmate death on March 30.17 The average incubation period after exposure to the virus is 5.1 days18 and the time to death is estimated to be 17.8 days.19 Thus the infection was likely present and spreading within the Stateville Correctional Center in early- to mid-March.

Confirmed cases are reported by facility but not the number of tests performed. This makes it difficult to gauge risk to the inmate population or to the communities surrounding correctional facilities where their workforces reside. A decline in COVID-19 confirmed cases may be due to declining transmission or to a lack of testing.

Since June 22, IDOC has reported only a handful of additional cases. Without sufficient testing, it is difficult to know the breadth of the infection among inmates. The Southern Illinoisan newspaper in Carbondale reported that less than 2 percent of inmates were tested by early May.20 As of June 9, IDOC indicated that only about 900 inmates had been tested for COVID-19.21 Overall, however, IDOC inventory reports show the number of COVID-19 tests in each facility’s inventory. Just over 2,900 tests showed as available to all IDOC facilities on June 17 for more than 30,000 prison inmates.22

The number of tests is dwarfed by needs. Consider East Moline which reported an outbreak of 28 cases among inmates and four among staff on June 22.23 The facility houses 1,055 inmates.24 Their inventory shows 110 tests since the May 19 report, up from 24 tests on April 30.25

Testing is an essential tool to preventing transmission between corrections and the general population in surrounding areas.

It is vital to explore ways to minimize risk of transmission between corrections and surrounding communities. Adequate testing of inmates and staff is needed not only to contain transmission among detainees but also to prevent spread to staff who likely live near the facilities. Of course, testing can also assist local communities with early detection of an outbreak.26

Figure 1 data sources and text accessible graph Heading link

Outbreaks in Illinois correctional facilities, continued. Heading link

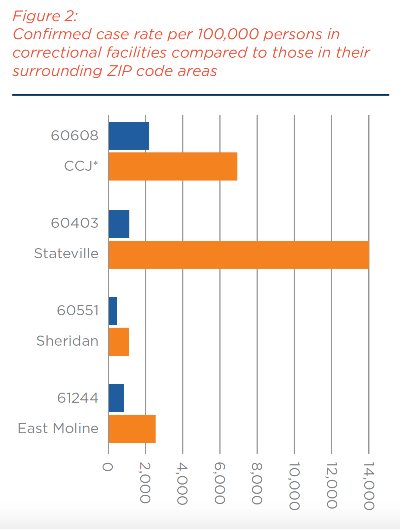

COVID-19 cases have been confirmed to have occurred in 101 of the 102 Illinois counties, as of June 22.27 Certain communities are sites of prisons that are near or over capacity.28 This includes Graham Correctional Center in Hillsboro, Stateville Correctional Center in Joliet, and the prison in Dixon. COVID-19 outbreaks, if not contained, could spread through the community in which officers and staff reside. Figure 2 compares the COVID-19 confirmed case rates at CCJ and at certain IDOC facilities with the highest COVID-19 case rates against the case rates in the ZIP code areas where these facilities are located.

In Will County, where Stateville Correctional Center is located, the facility’s 266 COVID-19 confirmed cases (187 confirmed inmates and 79 confirmed staff cases) made up 4.2 percent of the county’s total confirmed cases on June 22.29 Further, Stateville’s case rate of 16,447 per 100,000 persons is 18 times higher than that for Will County, which has a case rate of 906 per 100,000 (6,260 cases for a population of 690,743).30 The Stateville Correctional Center represents a hotspot within the county, similar to prisons in other states, including Ohio and New York.

Figure 2 suggests that curbing COVID-19 transmission within correctional settings would prevent community spread in surrounding areas that are relatively unaffected by the infection. In addition, jails can be a unique setting to identify individuals with COVID-19 infection coming into the jail and intervene, which can contribute to reducing com- munity transmission. The converse is also true: it is important to stop the spread of virus from a surrounding community into the correctional facility itself.

As we note below, honing in on where confirmed cases in specific facilities far exceed the rate in surrounding communities can guide the allocation of tests to prevent the transmission of COVID-19 from within the prison walls to neighboring com- munities. Likewise, where the confirmed case rate outside a prison is higher than that for the prison, adequate testing of correctional officers and staff can help prevent spread into the prison.

Figure 2 data sources and text accessible graph (as of June 19, 2020) Heading link

Conditions in other states Heading link

As in Illinois, prisons and jails are sites of concen- trated outbreaks in other states. According to the New York Board of Corrections (NYBOC), as of June 4, 343 inmates had been confirmed to have COVID-19 and three had died, which accounted for 8.6 percent of New York’s inmate population.31 Also on June 4, 197 NYBOC staff were under quaran- tine or confirmed positive, bringing the total of NYBOC staff confirmed cases to 1,408 or 12.8 percent of the NYBOC staff of 10,977.32

NYBOC’s reports do not include cumulative inmate confirmed cases, but Rikers Island in New York had confirmed 362 inmate cases by May 15, which represented 9.2 percent of Riker’s inmate population of 3,917.33 An additional 783 members of Rikers’ staff or 7.5 percent of Rikers’ employees, also had been confirmed to be positive as of April 21.34

Some states have implemented testing throughout their inmate population, including asymp- tomatic inmates. By late April, Ohio’s correctional facilities had 2,400 confirmed inmate cases, representing 5 percent of the state’s prison population.35 An additional 244 staff also tested positive. Together, the inmate and staff cases represented one-fifth of the 12,919 confirmed cases across Ohio by mid-April.36

Some correctional facilities in other states are testing every inmate for antibodies to the virus that causes COVID-19, which indicate past infection.37 They are finding that confirmed case rates fall well below rates of positive antibody tests. Consider Parnall Correctional Facility in Michigan, which houses 1,446 inmates. As of June 15, it had reported 505 confirmed cases and 10 deaths in its inmate population (35.6 percent of the inmate population).38 When the Michigan Department of Corrections tested 1,248 inmates at Parnall on May 22, 1,148 inmates, or 92 percent, tested positive for antibodies, suggesting that they had COVID-19 in the past.39

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention caution that testing positive for antibodies to COVID-19 is not an assurance that a person will not later become infected with the virus again, a point we discuss below. It can take 1-3 weeks after infection—perhaps longer for some people—for the body to make antibodies, and there is insufficient evidence to show how much protection antibodies might provide or for how long.40

Proposals to mitigate the impact of COVID-19 on inmates and surrounding communities Heading link

Approaches to mitigate the impact of COVID-19 in Illinois’ prisons and jails span several proactive measures. These range from containing the infection to distributing scarce resources like tests to assisting inmates with maintaining social ties in a time of stress, fear and loneliness. We explore a number of possibilities at the links below.

Mitigation analyses Heading link

Conclusion Heading link

Jails and prisons have become hotspots of COVID-19 across the country. The divergent in- fection rates in correctional settings have been a concern since the beginning of the pandemic. The reports from prisons and jails around the country underline the vulnerability of the incarcerated population and correctional staff to COVID-19. Indeed, some Illinois jails and prisons experienced disproportionately high rates of COVID-19.

IDOC will need to implement preventive mea- sures to protect the health of inmates and staff, as well as the community. Targeted testing will allow state officials to understand the severity of the localized outbreaks in jails and prisons, and intervene in a timely manner. Some Illinois prisons show lower levels of COVID-19 cases compared with the rate for the surrounding ZIP code areas. For these places, it is also critical to implement strategies to limit the possibility that staff might transmit the virus to inmates.

The risk at correctional facilities largely untouched by COVID-19 can still be managed before the dis- ease reaches the heights seen at the Cook County Jail and Stateville Correctional Center. IDOC pris- ons are not entirely removed from the community. Not only will the incarcerated populations and staff working in them be at risk for exposure, but the communities that surround them will as well. Large-scale testing and other mitigation efforts in the Illinois corrections system could ease that risk.

Additional information Heading link

On July 4, 2020, the Cook County Sheriff’s Department provided, via email, data concerning the daily and cumulative numbers of tests conducted and positive tests. We compiled several data tables from that data and present them here. The department’s own reports indicate that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention conducted testing that began on May 1, 2020 and ended on May 19, 2020. In addition, asymptomatic testing began on April 16, 2020. The Sheriff’s Department now provides a graph of this data at its website. Please view the most recent data at page 13 of the PDF version of the report.

About the authors Heading link

- Sage Kim, PhD, is an associate professor of health policy and administration at the University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC) School of Public Health.

- Timothy Jostrand is a 2019 graduate of the MPH in Health Policy and Administration program at the UIC School of Public Health.

- Ali Mirza is the Wolff Intern with the University of Illinois system’s Institute of Government and Public Affairs.

- Robin Fretwell Wilson, JD, is the director of the Institute of Government and Public Affairs.

Acknowledgement

We are grateful to Professor Andrew Leipold of the University of Illinois, College of Law for his thoughtful comments and to University of Illinois student Adem Osmani for his technical assistance with this Policy Spotlight.

COVID-19 Hub Page

References Heading link

- Curtis Black, “Illinois Prisons – and Rural Healthcare Systems – Facing Crisis Due to Slow COVID-19 Response,” Chicago Reporter, April 3, 2020, accessed June 22, 2020.

- Cook County Sheriff’s Department, “COVID-19 Cases at CCDOC,” June 22, 2020, accessed June 23, 2020.

- Ibid.

- Phone call, Cook County Sheriff’s Department, June 15, 2020; See also Pascal Sabino, “181 Cook County Jail Staffers Have Coronavirus. Remaining Guards Are Overworked, Forced To Cut Corners, Union Says,” Block Club Chicago, April 14, 2020, accessed June 15, 2020.

- Mays v. Dart, No. 20 C 2134 (N.D. Ill.), May 29, 2020, accessed June 23, 2020.

- Reinhart, Eric and Daniel Chen, “Incarceration and Its Disseminations: COVID-19 Pandemic Lessons from Chicago’s Cook County Jail,” Health Affairs 39(8):1-5, June 4, 2020, accessed June 15, 2020.

- Sage J. Kim and Wendy Bostwick, “Social Vulnerability and Racial Inequality in COVID-19 Deaths in Chicago,” Health Education Behav., May 21, 2020, PMID:32436405, DOI: 10.1177/1090198120929677.

- Grace Hauk et al., “Coronavirus Spares One Neighborhood but Ravages the Next. Race and Class Spell the Difference,” USA Today, May 20, 2020, accessed June 15, 2020.

- Illinois Department of Corrections, “Director’s Memorandum to Men and Women in Custody,” June 9, 2020,accessed June 22, 2020.

- Illinois Department of Corrections, “COVID-19 Response Table,” April 30, 2020.

- Illinois Department of Corrections, “COVID-19 Response Table,” May 12, 2020.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- State of Illinois, “Coronavirus (COVID-19) Response,” accessed June 23, 2020.

- llinois Department of Corrections, “Stateville Correctional Center,” inmate population as of April 22, 2020, accessed June 23, 2020.

- Illinois Department of Corrections, “Operations and Management Report Key Variables, Fiscal Year 2020,” accessed June 23, 2020.

- Carlos Ballesteros, “1st Illinois Prison Inmate Dies of COVID-19, Health Officials Say,” Chicago Sun-Times, March 30, 2020, accessed June 23, 2020.

- Stephen A. Lauer, et al., “The Incubation Period of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) from Publicly Reported Confirmed Cases: Estimation and Application,” Annals of Internal Medicine. 2020:doi: 10.7326/M7320-0504, accessed June 23, 2020.

- Robert Verity, et al., “Estimates of the Severity of Coronavirus Disease 2019: A Model-based Analysis,” Lancet, 2020; S1473-3099(20): 30243-30247, accessed June 23, 2020.

- Molly Parker, “Illinois has Tested Fewer than 2% of Inmates for COVID-19,” The Southern Illinoisan, May 9, 2020, accessed June 22, 2020.

- Illinois Department of Corrections, “Director’s Memorandum.”

- Illinois Department of Corrections, “Master Medical Inventory,” June 17, 2020, accessed June 22, 2020.

- Illinois Department of Corrections. “COVID-19 Response Table,” June 22, 2020, accessed June 23, 2020.

- Illinois Department of Corrections, “East Moline Correctional Center,” inmate population as of April 22, 2020, accessed June 23, 2020.

- Illinois Department of Corrections, “Master Medical Inventory,” historical statistics on file with authors.

- Greg Bishop, “Some Raise Concerns about COVID-19 Testing Policies for People Leaving Prison,” The Center Square, May 12, 2020, accessed June 23, 2020.

- Illinois Department of Public Health, “COVID-19 Statistics,” accessed June 22, 2020.

- Illinois Department of Corrections, “Correctional Facilities,” inmate populations as of April 22, 2020, accessed June 23, 2020.

- Will County Health Department and Community Health Center, “Novel Coronavirus, COVID-19,” June 19, 2020.

- U.S. Census Bureau, “Quick Facts, Will County, Illinois,” accessed June 22, 2020.

- New York City Board of Correction, “Daily COVID-19 Update,” June 4, 2020, accessed June 22, 2020.

- The Legal Aid Society of New York City, “Analysis of COVID-19 Infection Rate in NYC Jails,” June 5, 2020, accessed June 22, 2020.

- New York City Board of Correction, “Daily COVID-19 Update,” May 15, 2020, accessed June 22, 2020.

- Alleen Brown, “Inside Rikers: An Account of the Virus-Stricken Jail from a Man Who Managed to Get Out,” April 21, 2020, accessed June 23, 2020. The Legal Aid Society, “COVID-19 InfectionTracking in NYC Jails,” June 18, 2020, accessed June 22, 2020.

- 34 Ohio Department of Rehabilitation and Correction, “COVID-19 Inmate Testing,” April 19, 2020, accessed June 22, 2020, https://perma.cc/ZKC4-23XS.

- Bill Chappell and Paige Pfleger, “73% of Inmates at an Ohio Prison Test Positive for Coronavirus,” National Public Radio, April 20, 2020, accessed June 22, 2020.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Test for Past Infection (Antibody Test),” accessed June 23, 2020.

- Michigan Department of Corrections, “Total Confirmed Prisoner and Staff Cases to Date by Location,” June 15, 2020, accessed June 15, 2020.

- Angie Jackson, “Almost Everyone at One Michigan Prison Tests Positive for COVID-19 Antibodies,” Detroit Free Press, May 28,2020, accessed June 22, 2020.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Test for Past Infection.”

- Samantha Scotti, “Health Care In and Out of Prisons,” State Legislatures Magazine, September 2017, accessed June 22, 2020.

- Estelle v. Gamble, 429 U.S. 97, 103-04 (1976) (“An inmate must rely on prison authorities to treat his medical needs; if the authorities fail to do so, those needs will not be met. … The infliction of such unnecessary suffering is inconsistent with contemporary standards of decency as manifested in modern legislation codifying the common-law view that ‘[i]t is but just that the public be required to care for the prisoner, who cannot by reason of the deprivation of his liberty, care for himself.’”), Legal Information Institute, accessed June 22, 2020.

- Dean v. Wexford Health Source et al, Docket No. 3:17-cv-03112 (C.D. Ill. Apr 21, 2017), Court Docket.

- U.S. District Court, Central District of Illinois, Springfield, Civil Docket for Case No. 3:17-cv-03112-SEM-TSH.

- Bruce Rushton, “Six-Figure Settlement in Prison Lawsuit,” Illinois Times, Sept. 17, 2015, accessed June 22, 2020.

- Henderson v. Sheehan, 196 F.3d 839, 845 (7th Cir. 1999); Mathis v. Fairman, 120 F.3d 88, 91 (7th Cir.1997).

- Lippert v. Baldwin. ACLU of Illinois, 2020.

- Lippert v. Baldwin, Case: 1:10-cv-04603, U.S. Dist. Ct. Ill. N. Dist. E.Div. “Consent Decree,” May 19, 2019, accessed June 20, 2020. See also “Major Agreement Reached to Overhaul Inadequate Health Care in Illinois Prisons,” ACLU of Illinois, Jan. 3, 2019, accessed June 20, 2020.

- Shannon Heffernan, “Poor Medical Care Leads to Preventable Deaths In Illinois Prisons,” WBEZ Chicago, Nov. 15, 2018, accessed June 20, 2020.

- Lippert v. Baldwin, Sect. II, Item A.

- John Howard Association, “COVID-19 Survey: Report on Initial Results of Surveys Collected from People Incarcerated in IDOC Prisons,” accessed June 22, 2020.

- Ibid.

- John M. Raba, “Consent Decree, First Report of the Monitor,” Case No. 1:10-cv-04603, page 4, filed Jan. 13, 2020, accessed June 22, 2020.

- Ibid, pp 4-5.

- Lippert v. Baldwin, Case: 1:10-cv-04603, p 5, p 17, General Requirements.

- Illinois Department of Corrections, “Frequently Asked Questions,” accessed June 23, 2020.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Older Adults,” accessed June 23, 2020.

- Lippert v. Baldwin, Sect. III, Sub-sect. M, Para. 2.

- Raba, “Consent Decree, p 8.

- Ibid, p 47.

- Ibid, p 8.

- Ibid.

- Eleanore Tabone, “Exclusive: Prisoner with COVID-19 Describes ‘Unsanitary’ Conditions for Sick Inmates at IL Prison,” WQAD-TV, May 20, 2020, accessed June 23, 2020; See also Patrick Smith, “Degradation, Neglect and Roaches: Inside Illinois’ Largest Women’s Prison,” WBEZ-FM, Jan. 2, 2020, accessed June 23, 2020.

- Sarah Lazare, “Illinois Prisoners Say They Don’t Have Access to Hand Sanitizer, Cleaning Supplies or Soap,” In These Times, March 19, 2020, accessed June 20, 2020.

- Annie Sweeney and Megan Crepeau, “Alarm Grows as Cook County, State Struggle with What To Do with the Incarcerated in the Face of COVID-19,” Chicago Tribune, March 31, 2020, accessed June 22, 2020.

- Raba, “Consent Decree,” p 4.

- Lyndsay Jones, “Coalition’s Seeks Hand Sanitizer Donations for Illinois Prisons,” WCIA-TV, April 6, 2020, accessed June 22, 2020.

- Teresa Cordova and Steven Weine, “Mobilizing Community and Family Resilience Across Illinois,” Institute of Government and Public Affairs, University of Illinois System, April 16. 2020.

- Josiah Bates, “Ohio Began Mass Testing Incarcerated People for COVID-19,” Time.com, April 22, 2020, accessed June 23, 2020.

- Ariel Trocino, Sage Kim, et al., “Jails and Prisons Could Become Coronavirus Disaster,” Chicago Sun Times, March 26, 2020, accessed June 22, 2020.

- Zusha Elinson and Deanna Paul, “Jails Release Prisoners, Fearing Coronavirus Outbreak,” Wall Street Journal, March 22, 2020, accessed June 22, 2020.

- Parker Perry, “More than 300 Inmates of the Montgomery County Jail Accused of Non-Violent Crimes Have Been Released Since the Coronavirus Outbreak,” Dayton Daily News, March 25, 2020, accessed June 22, 2020, .

- Sonia Moghe, “Inside New York’s Notorious Rikers Island Jails, ‘The Epicenter of the Epicenter’ of the Coronavirus Pandemic,” CNN.com, May 16, 2020, accessed June 22, 2020.

- Money v. Pritzker, 1:20-cv-02093 (N.D. Ill.), filed April 2, 2020.

- Matt Masterson, “Lawsuit: Pritzker, IDOC Failed to Protect Vulnerable Inmates from COVID-19,” WTTW-TV, Chicago, May 21, 2020, accessed June 22, 2020.

- Illinois Department of Corrections, “Fiscal Year 2018 Annual Report,” page 82, accessed June 23, 2020.

- Victoria Moreno, Nancy Firfer, et al., “Re-Entry Housing Issues in Illinois.” metroplanning.org. The Chicago Community Fund.

- Steve Mills, “Why Illinois Keeps So Many Prisoners Incarcerated After Release Dates,” Chicago Tribune News Service, published at Governing.com, Jan. 25, 2015, accessed June 22, 2020.

- Office of Gov. J.B. Pritzker, “Executive Order 2020-13,” March 26, 2020.

- Office of Gov. J.B. Pritzker, “Executive Order 2020-24,” April 10, 2020.

- Office of Gov. J.B. Pritzker, “Executive Order 2020-21,” April 6, 2020.

- Nirmita Panchal, et al., “The Implications of COVID-19 for Mental Health and Substance Use,” Kaiser Family Foundation, April 21, 2020, accessed June 23, 2020.

- Bureau of Justice Statistics, “Reentry Trends in U.S.,” accessed June 22, 2020.

- Illinois Department of Corrections, “Visitation Rules and Information,” accessed June 22, 2020.

- Ibid.

- John Howard Association, “COVID-19 Survey,” Questions 13 and 14.

- Illinois Public Act 099-0878, Jan. 1, 2017, accessed June 22, 2020.

- Eric Zorn, “Illinois Now has the Lowest Prison Phone Rates in the Nation, and That’s a Good Thing,” Chicago Tribune, Jan. 24, 2019, accessed June 22, 2020.

- Prison Policy Initiative, “Illinois Profile,” accessed June 22, 2020.

- Prison calling rates, accessed June 23, 2020.

- Marion Fourcade, “The Political Valuation of Life,” Regulation & Governance, 2009:3, 291–297.

- Kendra Ogera, et al., “Urban and Rural Differences in Coronavirus Preparedness,” Petersen-KFF Health Tracker, April 22, 2020, accessed June 22, 2020; See also Kaiser Family Foundation, “Interactive Maps Highlight Urban-Rural Differences in Hospital Bed Capacity,” April 23, 2020, accessed June 22, 2020.

- Ricard Franki, “Rural ICU Capacity Could be Strained by COVID-19,” The Hospitalist, April 27, 2020, accessed June 22, 2020.

- Urban Data Visualization Lab, “COVID-19 Vulnerability Maps,” University of Illinois at Chicago, April 18, 2020, accessed June 23, 2020.

- Richard Florida, “Released Prisoners Struggle to Establish Neighborhood Connection,” Bloomberg.com, Aug. 23, 2018, accessed June 23, 2020.