Global Health Surveillance Improving Public Health

Story text

As the COVID-19 pandemic began washing over the world earlier this year, Dulal Bhaumik, PhD, had little interest in being a passive spectator. A biostatistician and professor in the UIC School of Public Health’s (SPH) Division of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Bhaumik assembled his team of graduate students (Sasha Kravets, Avisek Datta, Xiaohan Mei and Debarghya Nandi) and mapped out a plan for tracking the most significant and perplexing public health issue of the last 100 years. High-quality surveillance, he determined, was critical amid error-laden reporting systems and contradictory, if not downright puzzling, data.

The Bhaumik-led team began investigating confirmed COVID-19 cases and death rates as well as policies from six countries – China, Italy, Spain, France, South Korea and the U.S. Pouring into distinct data sources ranging from the World Health Organization to individual governments, Bhaumik noticed wide swings in confirmed cases and death rates from one country to the next. He questioned why, critically analyzing collection methods, reporting structures and policies.

In South Korea, for instance, Bhaumik witnessed a fatality rate far below that of nations such as Italy, Spain and France. Digging further, Bhaumik noted South Korean policies around universal testing and closed borders as well as an earnest national response to assemble personal protective equipment and other preventative aids such as hand sanitizer and antibacterial soap. “The results there didn’t come from the sky, so there must be systematic changes that were made,” Bhaumik said of South Korea in mid-April.

Into the spring, Bhaumik’s study, titled “Ever-Changing Statistics of COVID-19 and How It Moves,” continued. He explored differences in the outbreak pattern of COVID-19. He examined the role of temperatures, pH levels and humidity in slowing down the virus. He even analyzed potential connections between COVID-19 and a vaccine many south Asian countries use to safeguard children from tuberculosis. “We should know the truth,” Bhaumik said. “What are the trends? Who’s having success and what are they doing to control the spread of COVID-19?” Results of Bhaumik’s analysis were published in the Journal of Biostatistics & Biometrics in August 2020.

A necessary first step to inform decisions, guide action, evaluate interventions and, ultimately, improve public health, surveillance stands tall as a cornerstone of public health and a particular area of expertise across SPH and, specifically, within the School’s Global Health Program. Fostering research and public health practice in communities around the world, Global Health faculty are tracking gonorrhea in sub-Saharan Africa, improving workplace safety across multiple continents and bolstering the work of humanitarian organizations. According to Supriya Mehta, PhD, the Global Health Program’s interim associate dean, these ongoing surveillance projects position governments, public health agencies and their partners to craft more informed responses while also contributing to deeper understanding of prominent and pressing public health issues.

“Surveillance has many different and important utilities and is absolutely inherent in public health,” Mehta said. “Without sound surveillance data, it’s difficult to make decisions and evaluate policy.”

Surveillance to enhance safety

Since arriving at SPH in 2013 and spearheading the establishment of the UIC Mining Education and Research Center (MinER Center), Dr. Bob Cohen has been working both domestically and internationally to help industry, unions and government agencies improve their medical and health surveillance of workers exposed to mineral dust, specifically as it relates to respiratory disease. “This started with U.S. coal miners and led to the development of a footprint overseas,” explains Cohen, a pulmonologist who began studying coal miners and black lung disease in 1980 and confesses a love for “medicine and helping the underdog.”

Enhancing safety text, continued.

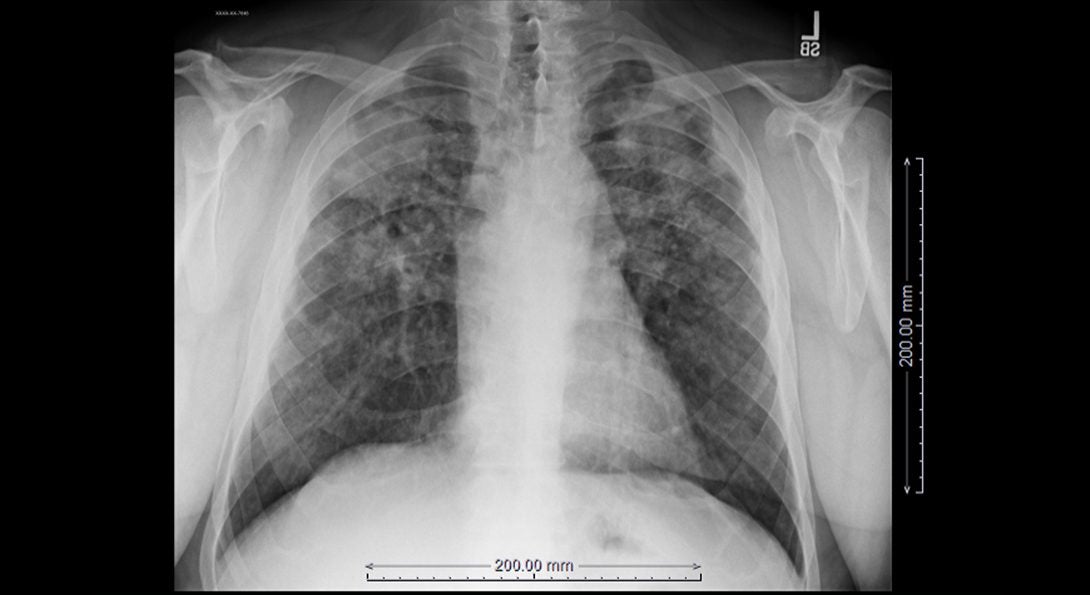

Over the last four years, in particular, Cohen and Division of Environmental and Occupational Health Sciences colleagues Drs. Leonard Go and Kirsten Staggs Almberg have been focused on coal miners in Queensland, Australia. While the Australians had touted the elimination of black lung disease in their mining populations for more than three decades, Cohen and his team uncovered deep flaws in the local surveillance program alongside several cases of black lung.

As a result, the Queensland State Government’s department of Natural Resources, Mining and Energy hired Cohen’s group to review the state’s entire surveillance program for miners, a substantial effort that included reading some 65,000 chest x-rays and revamping health surveillance training. Today, Cohen’s group is actively consulting with government on new rules and regulations designed to spur more effective primary and secondary prevention of black lung disease as well as improved screening and treatment measures.

“We want to make sure we’re doing our best by this workforce and these workers,” said Cohen, who has also developed medical surveillance protocols for miners in Columbia and studied other vulnerable labor groups such as stone fabricators and construction workers.

In February, the MinER Center co-sponsored an international union conference in Australia called “Cut the Dust.” The event, which featured mining, maritime and construction union health and safety representatives from multiple continents, explored ways to improve surveillance for disease, regulations for dust controls and various other health and safety issues. “Surveillance is that critically important way of taking a temperature of a population and evaluating workplace hazards so you can make decisions that improve health,” Cohen said. “Without surveillance, you’re left with more questions than answers.”

Surveillance to guide improved operations

Earlier this year, Dr. Rohan Jeremiah, an Associate Professor of Community Health Sciences, began consulting with the executive committee of the nonprofit Grenada Red Cross Society (GRCS) on the development of a five-year strategic plan. While GRCS held a clear mission – “To serve humanity through the promotion of health and safety, disaster preparedness and response, social welfare and youth programs.” – Jeremiah quickly observed that the organization had no surveillance structures in place to ensure GRCS could effectively and efficiently accomplish that mission. “We needed to build the organization’s capacity through routine data collection and analysis so that they could have a strong sense of community needs, whether that’s access to clean water or the availability of basic safety products,” Jeremiah said.

In March, Jeremiah ventured to the Caribbean nation to begin the first phase of the consulting project: conducting a SWOT (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats) analysis to better understand the needs and desires of the communities GRCS serves. In May, he then presented a report to the GRCS executive committee centered on routine data collection and analysis. He championed surveillance activities as a critical step to identifying community needs and informing how GRCS prepares and responds to communities following natural disasters and, at present, COVID-19. “The end game is helping them establish the surveillance structures, developing them and then providing training at the agency and community level so GRCS can be proactive, forward-thinking leaders ready to mobilize their resources,” Jeremiah said.

Working in Grenada since 2008 and having had other Caribbean nations adopt some of his surveillance-minded work as a template to combat violence, substance abuse and HIV/AIDS in their own countries, Jeremiah’s recent work with GRCS serves another example of the crucial role surveillance activities play in improving humanitarian and public health efforts. “Surveillance is the key first step,” Jeremiah said. “If we know what’s needed, the pain points, the resources available, then you’re ready to move and better positioned to be successful.”

Surveillance to support a promising clinical trial

In India and southeast Asia, nearly 200,000 suicide attempts per year involve the ingestion of rodenticides and pesticides. For those cases that do not result in death, the lingering existence of these poisonous toxins in the body can result in long-term behavioral and motor deficits. It’s a troubling reality and one Dr. Ron Hershow, director of SPH’s Division of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, stands eager to confront.

Alongside peers from the UIC College of Medicine, Hershow is currently involved in a nascent effort in India that aims to examine the effectiveness of the FDA-approved drug Cholestyramine (CSA) – a bile sequestrant originally used to reduce cholesterol levels – to increase the clearance of toxins from the body and reduce mortality rates, something the research group has already proven successful in animal models. “This will result in overall reduction in medicines needed for long-term treatment, reduce hospital readmittances due to reappearance of symptoms, reduce the time needed for at home follow-up care and may reduce long term behavioral deficits,” Hershow said of his team’s promising work and the “worthy goal” of quickly ridding the body of these damaging toxins.

While the COVID-19 pandemic paused the upstart efforts of Hershow and his collaborators, the group nevertheless continued to solidify its research plans and on-the-ground partnerships in India throughout the first half of 2020. As the research team’s epidemiologist, Hershow’s immediate charge is to design enrollment procedures that leverage existing surveillance systems, namely India’s poison registries, to identify new onset cases and then channel potential enrollees into the proposed clinical trial. He will also be tasked to craft methods to gauge efficacy during the clinical trials and analyze data for publication.

By following, tracking and mapping cases, Hershow’s surveillance work will help his research team better pinpoint problem areas, allocate resources and test interventions. “You see a problem, develop solutions, evaluate how they work and continue to fine-tune interventions so you’re having maximum impact,” Hershow said. “That’s why surveillance work is so rewarding.”

“These projects reflect the critical role of surveillance in global public health and how surveillance is used for planning and evaluation, health systems response, and policy development,” Mehta concludes. Dr. Mark Dworkin, Professor of Epidemiology & Biostatistics, teaches the popular Public Health Surveillance course where students gain insight on conceptual and technical aspects of surveillance. The course fosters critical skills in surveillance to prepare the next generation of public health leaders, practitioners, and researchers to combat global health challenges. “To adapt to emerging public health threats, we need innovative and multifaceted surveillance approaches with community and governmental partnerships. Our faculty and students are leading the way in this changing landscape to improve and accelerate surveillance approaches for improved public health response,” says Mehta.