Contact Tracing for Communities of Color

Story text

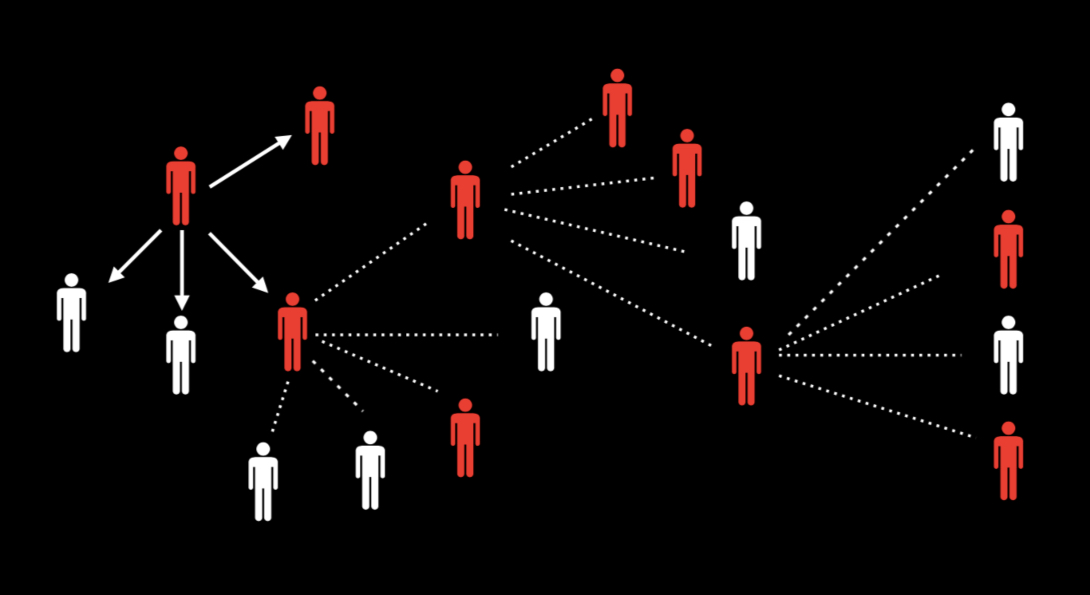

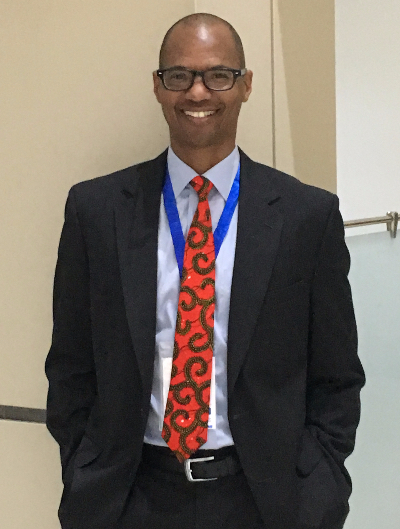

The Community Outreach Intervention Projects (COIP) at the University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC) School of Public Health pioneered the indigenous leadership outreach model in the 1980s, equipping trusted local community leaders with health messaging on topics like safe injecting and safe sex. In the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, alumnus Philip Ricks, PhD in Epidemiology ’08 and MPH in Epidemiology ‘96, is building on this model to design contact tracing capacity for communities of color.

As a global disease dectection analyst at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Ricks is collaborating with colleagues at I-LEAD, a community-based leadership training organization, UPHOLD, a scholarly activists cooperative focused on health disparities, and students and faculty from several universities, including the UIC School of Public Health, to build a curriculum for training contact tracers that addresses the specific needs of Black and Latinx populations hit hard by the pandemic.

This is an opportunity to really look at health inequities in Black and Brown communities and let this be a platform for addressing some of those underlying issues, Ricks said. COVID is simply the entry point.

Ricks notes that contact tracing is a well-established concept but adding in elements of cultural competency will create an entirely new product. An immediate barrier is inherent distrust in communities of color toward healthcare due to experienced biases and mistrust of authority. Ricks, who worked with COIP while a student at UIC, says contact tracers need training in speaking to people from different cultures and skills in practicing cultural humility. With the sheer volume of tracers needed in this pandemic, Ricks says identifying people who can leverage the capital they have already built in their communities will be key to building capacity.

He envisions a model that goes far beyond simply identifying possibly infected individuals. Hypertension, obesity and hypercholesterolemia, among other social determinants, are driving high rates of mortality in communities of color, and a tracing approach needs to be comprehensive to begin building solutions to these inequities. Ricks says this outreach model should also stress the need for flu shots, the involvement of people of color in vaccine trials and ways to build sustainable health outreach employment in affected communities.

Ayokunle Olagoke, PhD in Community Health Sciences student, is part of the nationwide network of researchers building the curriculum. She says social determinants of health like reaching homeless populations, overcrowded living conditions, practicing physical distance in public-facing jobs and underinsured or uninsured populations demonstrate that tracing cannot stop at identifying human vectors for the virus.

Selected Quote

Some people may lose their jobs if they take a day off to attend to their health, so they don’t want to disclose their status. The obvious truth is that this pandemic is not affecting everyone in a uniform way, so wisdom dictates we offer a tailored approach in our response to contact tracing.

| PhD in Community Health Sciences student

Story text, continued.

Vaccine education should be a critical function for contact tracers, Olagoke says. Due to limited knowledge on how vaccines work and lack of trust in government, specific vulnerable communities have mixed feelings toward the idea of a future COVID-19 vaccine. At the same time, these populations have experienced direct and secondary trauma from high rates of infection and mortality in their local communities, requiring contact tracers to acknowledge stigma in contact tracing and manage trauma.

“This is really a chance to engage the community instead of the community being acted upon,” Ricks said. “This is the chance to empower the community to develop their own resources and leave something behind that is sustainable.”