Honoring Dr. Samuel Epstein’s mission

A new family-supported scholarship fund supports SPH students investigating environmental exposures and cancer links

Story text Heading link

In Chicago, community members are increasingly involved in public health decision-making on industrial environmental exposures in and near city neighborhoods. The efforts of these citizen scientists are a natural outgrowth of the storied career of Samuel Epstein, PhD, professor of environmental and occupational health sciences from 1976 to 1999 at the School of Public Health.

Epstein was one of the first in the U.S. to issue a clarion call about carcinogenic risks of environmental and occupational exposures. From ccollaborations with Ralph Nader to his leadership of the Rachel Carson Trust for the Living Environment, Epstein’s claims were often met with ridicule by industry and even some fellow scientists, but his dogged scholarly approach ultimately bore witness to an emerging awareness of environmental health risks across the country.

“He was rigorous with the data and was one of the first, if not the first, to understand that we were introducing massive amounts of synthetic chemicals into the environment without any data proving their safety and significant data suggesting their dangers,” said Julian Epstein, one of Samuel’s sons. “All of this was reaching our bloodstreams and organs on a massive scale unprecedented in human history. He was the proverbial canary in the coal mine.”

Julian and brother Mark Epstein are aiming to support SPH students who will highlight and address the next generation of environmental health challenges. Their gift of $60,000 will support six students in the division of environmental and occupational health sciences interested in environmental exposures and cancer prevention.

“Science and medicine have helped create important health and safety protections, but there are still environmental risks that need to be solved in our lifetime,” Mark Epstein said. “Corporate and economic influence, conflicts of interest and the rapid pace of innovation require more than ever that we’re supporting those stewards who are dedicated to finding solutions to address these harms.”

Kristen Malecki, PhD, director of the division of environmental and occupational health sciences, said the gift will support students engaging with new advances in public health science.

“New technologies are now providing tools to support much- needed research and awareness of the complex interactions between genetics, social and cumulative environmental factors that shape cancer,” Malecki said. “The generous gift from the Epstein Foundation will advance training of the next generation of scholars in cancer and environmental health sciences.”

Samuel Epstein’s research and accompanying warnings followed the post-World War II boom in the U.S., a period of significant technological and economic growth. Yet behind these leaps were a raft of newly created inorganic compounds with little testing before entering the marketplace. While Rachel Carson was decrying the use of DDT as a pesticide, Epstein began focusing on petroleum-based consumer products. Slowly but surely, he built a corpus of evidence that pointed to significant carcinogenic risks in the products that had redefined American life.

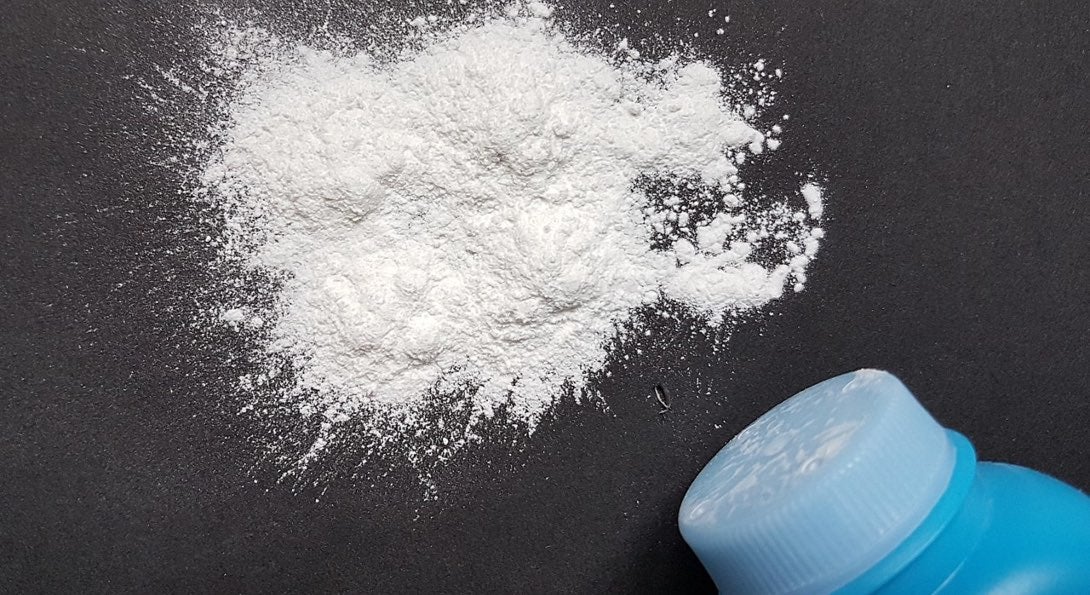

His 1978 book, “The Politics of Cancer,” ignited a firestorm of controversy, according to author Robert N. Proctor, describing an “indictment of industry malfeasance, research impotence and regulatory incompetence.” Epstein advocated on a wide range of issues, from Vietnam veterans exposed to Agent Orange to toxic waste dumps near U.S. communities to the risks of seemingly innocuous products like baby powder and toothpaste.

Julian and Mark Epstein both cite the infiltration of plastics in air, water supplies, oceans and in human bodies as one of challenges they envision environmental health leaders will be tackling in the near future. With the global scope of this challenge, Mark Epstein cites his father’s commitment to working with stakeholders from government agencies to clinicians and industry as keys to engaging in the political and economic decision-making that accompany environmental health research.

“He was a maverick in the sense that he understood that scientists had to be broader than their publications in scientific journals; they had to also participate in the public square as the solutions were ultimately and necessarily political,” Julian Epstein said. “We’re hoping this gift will inspire those who want to marry the rigors of scientific research with well-reasoned public policy. Ultimately, his message was a stitch in time saves nine – prevention in public health is a lot less expensive than getting sick with these deadly diseases. It’s as true today as it was when he first started.”