Commentary: COVID-19 Racial Disparities

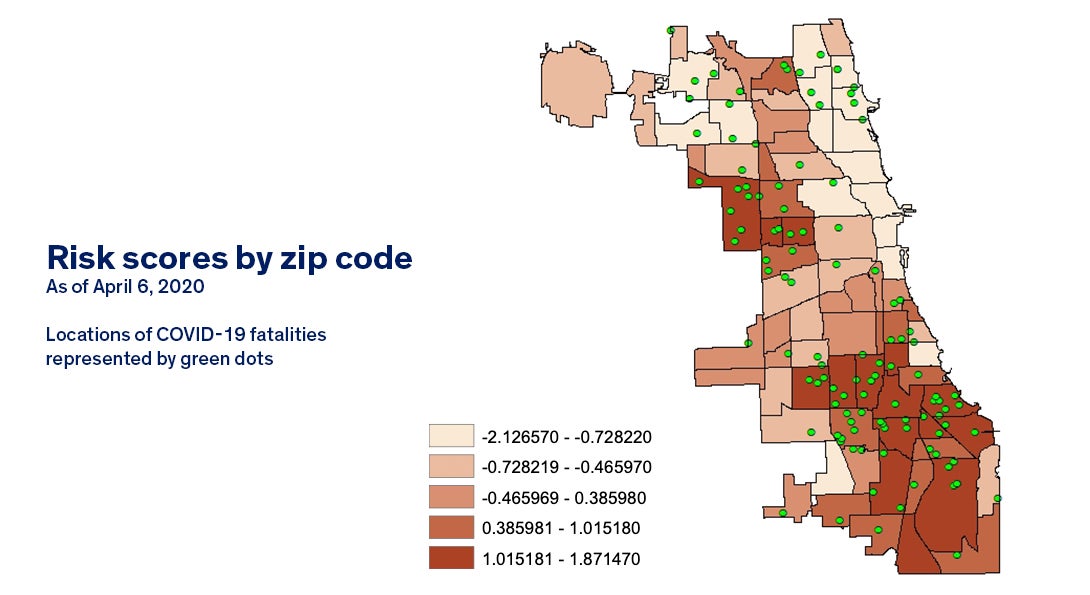

While we may all be in this pandemic together, public health professionals knew, communities of color would bare a disproportionate burden of the effects of COVID-19. To track the effects of systemic racism, public health experts examine data on infection and hospitalizations by race/ethnicity. On Monday, April 6, we finally saw these figures for Chicago, and they were not surprising.

While only 30 percent of Chicago’s population is Black, 72 percent of the city’s COVID-19 deaths were among Blacks Chicagoans. The spokesperson from the Chicago Mayor’s Office acknowledged this reality, saying “early community spread in Black communities and higher baseline rates of chronic underlying conditions are driving [these] issues.” Similar patterns can be seen in data released in Wisconsin, Louisiana, Philadelphia, Detroit and other cities and states.

This is not a surprise to public health professionals. In fact, it is predictable. Health— and the opportunity to be healthy—is rooted in complex social and structural inequities that unfairly advantage some and disadvantage others (Jones, 2014). Long before this pandemic emerged, racism and classism created the conditions in which this inequity was able to take hold. The lack of access to health care and health insurance, to quality education, and to decent jobs and financial stability has led to rates of diabetes, heart disease, and lung disease that are higher in communities of color than in their white counterparts. These are the very conditions that make COVID-19 so dangerous, illustrating the many ways that injustice can kill.

To address these systemic disparities, academic and public health professionals must engage in partnership with communities of color on research and action. Achieving health equity requires centering and elevating the voices and the leadership of those experiencing the inequities.

This is not easy work. Authentic, reciprocal academic-community partnerships take effort. Historical abuses by researchers and unfair practices have led many African Americans to believe that research findings will be used to further stereotype them, expose them to unnecessary risk, and not benefit the community at all (Corbie-Smith et al., 2002, Brandon et al., 2005; Corbie-Smith et al., 2004; Katz et al., 2006). This means that fewer African Americans participate in research, so we know less about the fidelity of health promotion interventions. Negative encounters with doctors, unequal access to care, and experiences with discrimination compound to reinforce beliefs that scientists and physicians cannot be trusted (Katz et al., 2006; Brandon et al., 2005). It is up to us - the academic and public health community - to earn that trust, and the way we do so is through inclusivity, mutual respect, and community engagement. This work must be done before crises happen, so that communities can be part of the response, rather than watching from the sidelines.

We applaud the City of Chicago’s partnership with West Side United to implement a strategy to reach out to residents and address “the realities of everyday life among those most impacted by COVID-19.” Across UIC, our academic and community partnerships are linking arms to maximize the impact of the city’s Racial Equity Response Team. As academic and public health professionals, we need to do more. We need to meaningfully invest in communities. We need to genuinely engage and build trusting partnerships. We need to transform our systems to create health justice.

What you can do as a public health professional Heading link

- Share factual information and data that have been vetted by reliable sources.

- Acknowledge and respond to the widespread mistrust and misinformation that some communities have.

- Mobilize existing community-campus networks to support the most vulnerable.

- Free up existing resources (funding, IT, information) that can be used to serve communities.

- Stay connected to partners through the Internet and phone.

- Integrate COVID-19 information in every message being sent out.

- Assist community health workers and other front-line staff in mitigating exposure.

- Listen to the concerns and challenges of the community

- Document the lessons learned – we will need them again.

- Use the moment to fight for the future.

Source: Community Campus Partnerships for Health

What you can do as a neighbor Heading link

- Support policies that require more people to stay home.

- Support legal and policy responses that address social determinants—both those that are root causes as well as immediate needs:

- Expand paid leave and other employment protections;

- Freeze evictions and utility shutoffs;

- Provide safe and healthy housing;

- Increase nutritional supports in low income communities;

- Direct financial support.

- Challenge policymakers to provide legal, social and financial protections to facilitate social distancing and isolation.

About the authors Heading link

Alexis Grant is a PhD in Community Health Sciences student at the University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC) School of Public Health and a community engagement fellow with the School’s Collaboratory for Health Justice

Jeni Hebert-Beirne, PhD, is the interim associate dean for community engagement at the UIC School of Public Health.

The Collaboratory for Health Justice at the University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC) School of Public health is dedicated to supporting faculty, students, and staff in reciprocal community engagement to improve our public health research, teaching, and practice. We strive to advance health justice—that all people would have the power and resources to have agency over their health, which requires addressing systems of oppression such as classism, racism, sexism and xenophobia. Our mission is to support academic-community partnerships by facilitating the meaningful participation of broad stakeholders; fostering representation & presence in academic settings; and providing training and technical assistance for integrating community engagement across research, teaching and practice.

Resources Heading link

- Engaged Research Partnerships During COVID-19: Staying True to Principles of Engagement in Community Engaged Research Partnerships during the COVID-19 Pandemic

- COVID-19 and Health Equity Resources. 2020. Health Equity Initiative

- Public Health Awakened and the Spirit of 1848 COVID-19 Resource Document

- The Praxis Project Principles for Health Justice and Racial Equity

Further reading and works cited Heading link

- Brandon, D. T., Isaac, L. A., & LaVeist, T. A. (2005). The legacy of Tuskegee and trust in medical care: is Tuskegee responsible for race differences in mistrust of medical care? Journal of the National Medical Association, 97(7), 951.

- Benfer, E.A. & Wiley, L. F. Health Justice Strategies to Combat COVID-19: Protecting Vulnerable Communities During a Pandemic. 19 Mar 2020. Health Affairs Blog.

- Colbert, Harry. 30 March 2020. COVID-19 highlights health disparities facing African-Americans. Insight News.

- Corbie-Smith, G., Thomas, S. B., & George, D. M. M. S. (2002). Distrust, race, and research. Archives of internal medicine, 162(21), 2458-2463.

- Corbie-Smith, G., Moody-Ayers, S., & Thrasher, A. D. (2004). Closing the circle between minority inclusion in research and health disparities. Archives of Internal Medicine, 164(13), 1362-1364.

- Jones, C. P. (2014). Systems of power, axes of inequity: parallels, intersections, braiding the strands. Medical care, S71-S75.

- Katz, R. V., Russell, S. L., Kegeles, S. S., Kressin, N. R., Green, B. L., Wang, M. Q., … & Claudio, C. (2006). The Tuskegee Legacy Project: willingness of minorities to participate in biomedical research. Journal of health care for the poor and underserved, 17(4), 698.

- Maxwell, Connor. 27 Mar 2020. Coronavirus Compounds Inequality and Endangers Communities of Color. Center for American Progress.

- Schiavo, Renata. 18 March 2020. COVID-19 is a Health Equity Issue. Health Equity Initiative Blog.

- White, L.E. & Zubak-Skees, C. Underlying Health Disparities Could Mean Coronavirus Hits Some Communities Harder. 1 April 2020. National Public Radio.