Environmental justice conditions for a proposed Pilsen-area metal recycler

Learn about degrees in environmental and occupational health sciences Heading link

Introduction Heading link

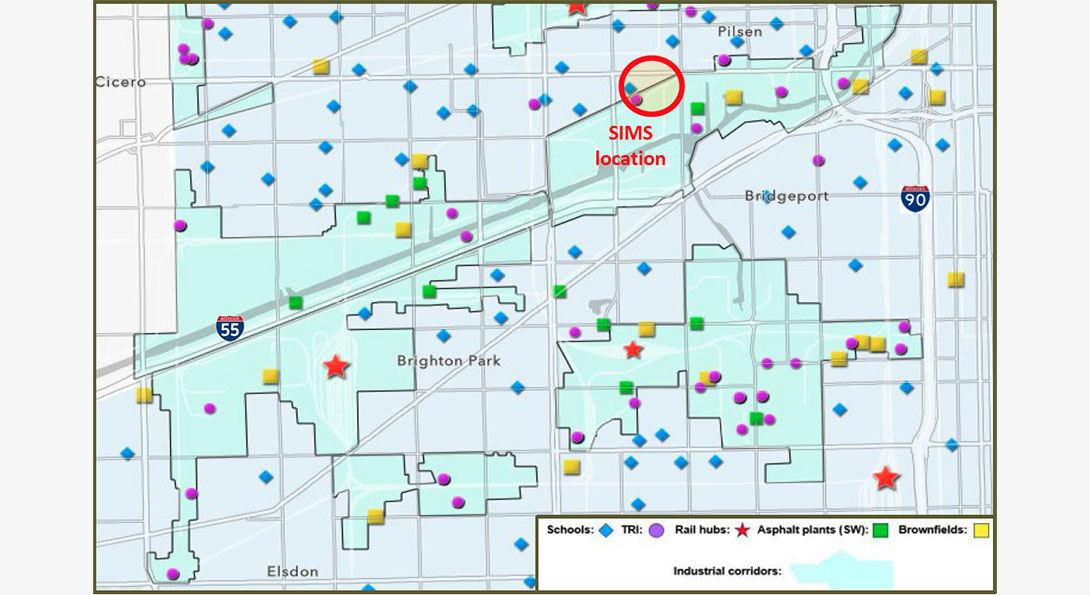

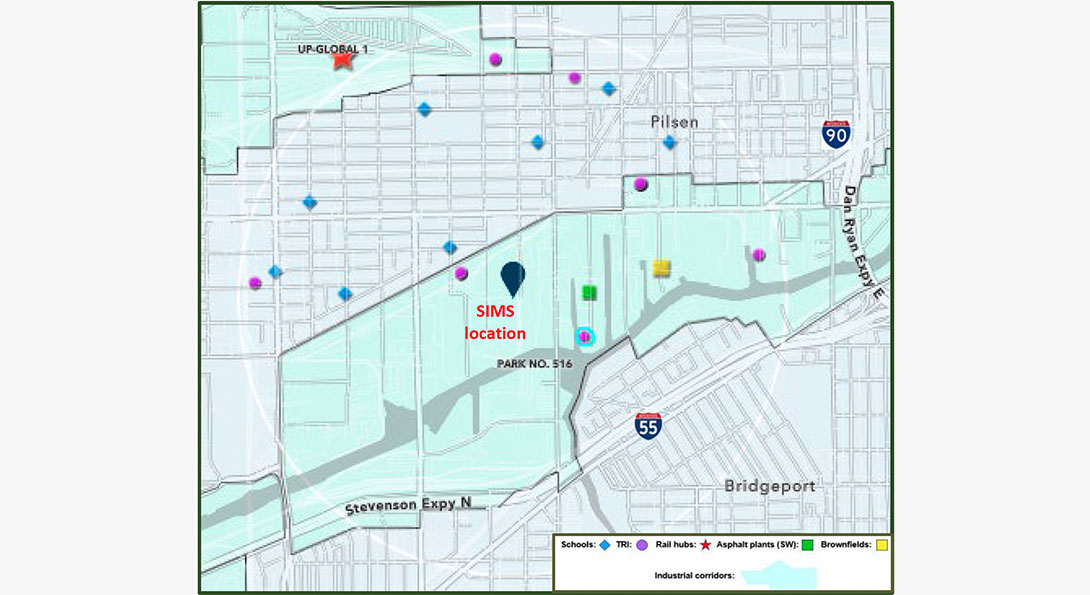

The site for the scrap metal recycling facility proposed for SIMS Metal is at the edge of the industrial corridor near the residential sections of Chicago’s Pilsen and Little Village neighborhoods. These two areas, and even more so Bridgeport, McKinley Park, and Brighton Park to the south, have a uniquely poor environmental justice (EJ) profile: a dense, predominantly Latinx residential sector, which is surrounded by industrial corridors and two major highways (See Figure 1). In addition, this part of the city has most of Chicago’s rail yards (six of the eight within the city limits), numerous storage and industrial facilities, brownfields, and many asphalt plants, all of which are a major nuisance for these communities.1,2,3

Report text Heading link

This issue has been covered in the two UIC studies made public as dashboards.1,2 A key finding of these is that Chicago’s toxic release inventory (TRI) reporting facilities are concentrated near neighborhood public schools in communities with a predominantly Latinx student population.1,2 The proximity of industrial facilities (at a TRI level), rail yards, and brownfields to public schools is a major issue that places these communities at an elevated EJ status since, to paraphrase the EPA’s fair treatment environmental justice definition:

no group of [children], should bear a disproportionate share of the negative environmental consequences resulting from industrial, governmental and commercial operations or policies.

In communities on the Southwest Side, 79.1 percent of the children in public schools come from below-poverty level households, mainly Latinx families, and already bear a disproportionate share of environmental consequences (e.g., proximity to TRI facilities and rail yards) compared to their peers across the city.1,2,3

View the interactive dashboard

Area demographics and environmental justice indicators Heading link

Demographic information from EPA’s Environmental Justice Screening and Mapping Tool (EJSCREEN) indicates that at a 1-mile radius around the proposed facility this area is a low-income neighborhood, with 82 percent of its residents being people of color (See Appendix). The environmental justice indicators from the same source reveal an area at the highest level of environmental justice charts, with indices reaching the top percentiles for specific hazards (See Appendix). For example, the index score is at the 97th percentile for the state of Illinois for both NATA Diesel PM (μg/m3) and Respiratory Hazards. These EPA findings underscore this area’s severe environmental justice status and corroborate the conclusions of the UIC studies.1,2

Potential cumulative impacts and hazardous sources Heading link

In assessing the environmental justice status, the UIC team has focused on the sensitive populations in the area (K-8 students). We note that the Chicago Department of Public Health (CDPH) is taking this into account in consideration for the siting of another facility in the southeast part of the City: “The proposed facility boundary is approximately 1,250 feet from the nearest residences and approximately 1,600 feet from George Washington High School and Rowan Park.” (Source: City of Chicago5)

As a screening tool, the UIC approach is to create a simple list of the overall hazardous sources to assess whether adding one more source is acceptable under the EJ principle of people (in this case children) sharing proportionately environmental consequences. Our dashboard provides a visualization of all these major sources that can potentially impact the schools.3

As seen in Figure 2, the new facility would be situated in a 3.14 square mile area that now contains:

- Eight Chicago public schools with 3,359 children.

- One asphalt plant (Reliable Ogden LLC).

- One brownfield

- Seven Toxic Release Inventory facilities (such as H. Kramer and Co.) that emit 18 toxic chemicals, including the carcinogens trichloroethylene, tetrachloroethylene, methyl isobutyl ketone, nickel, lead, and di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate.

Impacts and sources, continued. Heading link

Geographically, these eight schools are wedged between two industrial corridors (i.e., landscape burden). Three of the schools are less than 1-mile from the I-55 and I-90 expressways. These corridors are a major source of heavy truck traffic, serving the numerous industrial and storage facilities as well as being the operational location of diesel-powered material handling equipment known for their diesel particulate matter and oxides of nitrogen emissions.

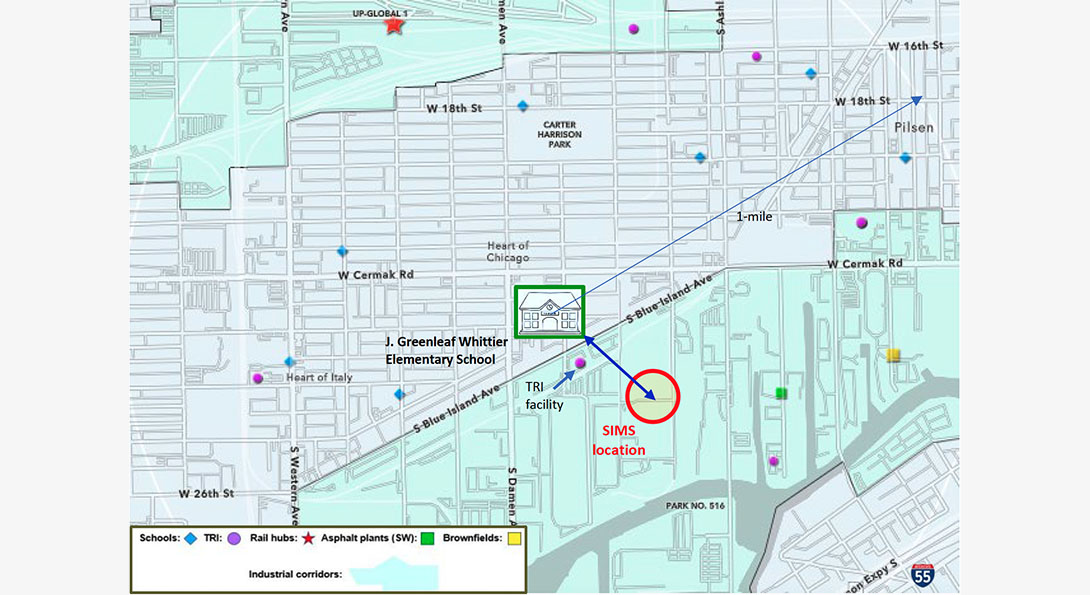

To assess the impact of adding a new facility in an EJ community, we examined the existing burden on the nearby schools. The John Greenleaf Whittier Elementary School is selected to demonstrate this approach. This School is approximately 1,575 feet from the proposed facility – a distance that would take the average person about five minutes to walk – if they could walk in a straight line. Table 1 is based on the pre-COVID 2016-17 Chicago Public Schools database and provides demographics and distance for the four closest schools.

K-8 schools closest to the facility Heading link

| School | Students | Low Income | Hispanic | Distance (feet) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| John Greenleaf Whittier | 299 | 92.1% | 99.1% | 1,575 |

| Peter Cooper Elementary Dual Language Academy | 459 | 88.7% | 96.9% | 3,051 |

| Irma C. Ruiz | 699 | 89% | 96.3% | 3,215 |

| Orozco Fine Arts & Sciences | 541 | 89.6% | 96.1% | 4,035 |

Schools analysis Heading link

By taking the adjacent schools as the reference point for a preliminary screening assessment, the UIC approach aligns itself with the “child-centered approach to cumulative risk assessment” promoted by the World Health Organization.6 Figure 4 shows the hazardous sources of concerns present in the immediate area of John Greenleaf Whittier, the selected example school.

Within a 1-mile radius of the Whittier school the following hazmat sources are found:

- Five TRI reporting facilities emitting 16 toxic chemicals, including the carcinogens trichloroethylene, tetrachloroethylene, methyl isobutyl ketone, nickel, lead, and di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate.

- One railyard (Union Pacific Railroad – Global I terminal).

- One asphalt plant (Reliable Ogden LLC).

- One brownfield.

- The landscape burden of being close to the industrial corridors to the north and south.

At a distance of only 565 feet from Whittier (a 2-minute straight-line walk) is a TRI reporting facility that emits tetrachloroethylene, trichloroethylene, and methyl isobutyl ketone – all known carcinogens. Because the existing permits for these facilities are not based on cumulative impacts or risks, the actual consequences and degree of environmental burden resulting from proximity to these multiple hazmat sources for the children living and going to school here cannot be fully known. The other schools in the zone share similar burdens, clearly demonstrating the high disparity in the distribution of potential environmental consequences across the city: many schools in northeast section of Chicago have no such hazmat sources near them.

The need for a cumulative impact assessment framework Heading link

The environmental justice status of the schools in this section of the city raises serious issues that cannot be overlooked, and which go beyond the emission levels of any existing or planned facility. The City has already recognized the need to implement a cumulative impact framework of assessment to protect children. This recognition leads directly to a decision pathway already envisioned by City leaders: implementation of a new cumulative impact ordinance for environmental justice communities.

The City shares the US EPA’s commitment to environmental justice and public health, and we look forward to partnering with them to conduct a fair, thorough and timely health impact analysis … At the same time, Mayor Lori Lightfoot directed the City’s Chief Sustainability Officer and the Department of Public Health to propose a new cumulative impact ordinance for consideration by the City Council before the end of this year, broadening its authority over air quality considerations, especially in Chicago’s more industrialized neighborhoods.7

Given the EJ status of the nearby schools in “industrialized neighborhoods,” it is clear that the best approach for siting new facilities is the cumulative impact ordinance that the City of Chicago is planning to implement. The importance of cumulative exposures is not something new. The concept has been well established since the Food Quality Protection Act (FQPA) of 1996, which required the US EPA to make cumulative assessments of the risks posed by exposures to pesticides. This law raised the awareness of such risks and led to the advancement and differentiation of cumulative risk and impact assessment methodologies. The US EPA details this approach and established “A Framework for Assessing Health Risks of Environmental Exposures to Children.”8 States such as California, have been using cumulative impact methodologies to assess the EJ status of communities since the early 2000s. Recently, the New Jersey State passed an environmental justice law (C.13:1D-159 to 161; September 18, 2020) that requires permit applications to have an environmental justice impact statement for the nearby overburdened communities. At a city level, the City of Newark, NJ made history when the City Council passed a first-in-the-nation Environmental Justice and Cumulative Impacts Ordinance in July 2016.

Conclusion Heading link

The recent 2022-2026 EPA Strategic Plan Draft provides a thorough statement of the underlying issues that overburdened communities face.

Many of the problems that need to be addressed have been well-known but unsolved for decades. Communities that have multiple industrial and energy facilities and are saturated with legacy pollution want to see EPA realign its enforcement in a way that provides action, accountability, and guidance for taking cumulative impacts and risks into account, even if they cannot be measured with precision.

Permitting and rulemaking have typically not reflected the reality of overburdened communities, which means that it is often easier to site an eighth facility in a community that already has seven than in a community that has none. Since permitting is primarily implemented by other governmental partners with delegated authority from EPA, the work of integrating environmental justice and external civil rights considerations throughout all EPA programs and activities will require commitment, relationship building, and trust from partner agencies.9

For overburdened communities in Southwest Chicago, their concerns, especially for children, can only be addressed using a cumulative impact framework for assessing the addition of one more facility near their children’s schools.

References Heading link

- Midwest Comprehensive Visualization Dashboard (MCVD EJ.1): Environmental Justice and Neighborhood Schools in Chicago, Illinois. Part 1.

- Midwest Comprehensive Visualization Dashboard (MCVD EJ.2): Environmental Justice and Neighborhood Schools in Chicago, Illinois. Part 2.

- Midwest Comprehensive Visualization Dashboard (MCVD EJ.3): A New Environmental Justice Tool for Chicago Communities.

- US Environmental Protection Agency. Environmental Justice. Last accessed, January 2022.

- City of Chicago. RMG Expansion on Southeast Side. Download Responses to questions raised during the hearing. Last accessed, February 3, 2022. Page 7 of 13

- World Health Organization. (2006). Principles for evaluating health risks in children associated with exposure to chemicals. World Health Organization.

- City of Chicago. RMG Expansion on Southeast Side. Last accessed, February 3, 2022.

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). (2006) A framework for assessing health risks of environmental exposures to children. National Center for Environmental Assessment, Washington, DC; EPA/600/R-05/093F.

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Draft FY 2022-2026 EPA Strategic Plan – October 1, 2021. Last accessed, February 3, 2022.